X-ray crystallography: A woman’s science? Part 1

Part 1

On the surface, the history of X-ray crystallography appears to be dominated by female figures, but is this really the case?

Crystallography, the experimental science used to discern the internal structure of crystals, has existed for hundreds of years, enabling advancements in medicine, mineral, and material sciences. Unusually, following the invention of X-ray crystallography in 1912, the field became known for its association with female scientists. At a time where women were overlooked and discriminated against in science, as well as in society at large, many female crystallographers were able to find employment and rise to international prominence. Their legacy has stood the test of time: in 2004, the distinguished crystallographer Judith Howard went so far to say that crystallography is “an area of science in which women dominate”.

But just how accurate is this assertion? Was crystallography really a feminist utopia?

In this blog, we’ll be delving into the achievements of the inspiring women who shaped X-ray crystallography and examining how far the experiences of these trailblazers differed from other disciplines, both in the 20th century and today.

The origins of X-ray crystallography

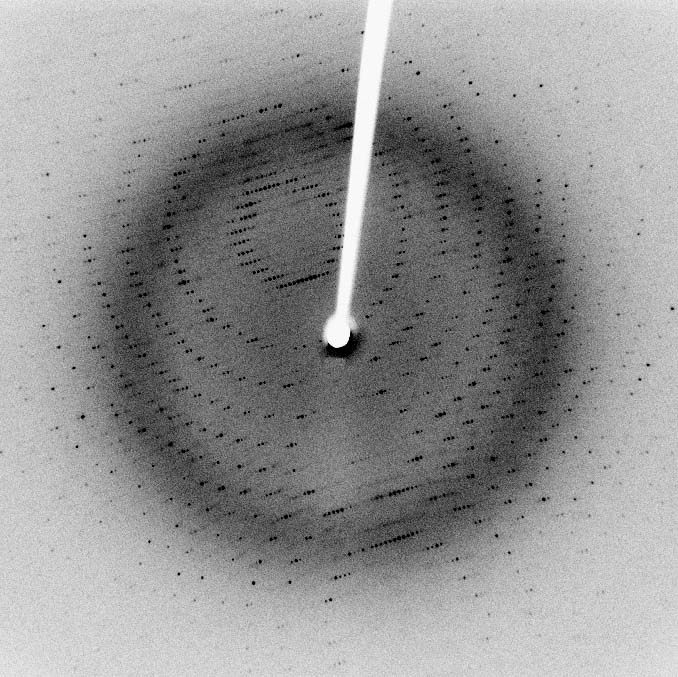

While the term ‘crystallography’ was officially coined in 1723, X-ray crystallography, the discipline’s central experimental technique, was first developed in the early 20th century. In 1912, William H. Bragg, a British physics professor, and his son Lawrence were informed while on holiday that a significant scientific event had occurred. The German physicist Max von Laue had produced a regular pattern of spots on a film by shining X-rays through a crystal, marking the discovery of X-ray diffraction in crystals.

The theory that crystals contained some inherent internal regularity had existed for some time. However, Laue’s discovery was hugely significant, for two main reasons. Firstly, it confirmed Laue’s prediction that the supposed regular arrangement of atoms within a crystal were approximate to the intervals of a diffraction grating, providing the basis for accurate structural analysis of crystal structures. And secondly, in doing so, Laue had proved that X-rays could be described as waves, finally settling a debate that had been raging since their discovery in 1895.

The Braggs were instrumental in building upon Laue’s work. Crucially, since the pattern that Laue had observed was the result of X-rays being reflected by regular planes of atoms, Lawrence Bragg inferred that it was possible to use this approach to determine the precise arrangement of atoms within crystal structures. Lawrence’s interpretation eventually gave rise to the famous Bragg’s Law of X-ray diffraction, which is still used today. For their pioneering work, the Braggs jointly won the Nobel Prize in 1915.

The Bragg Legacy

In addition to these ground-breaking achievements, the Braggs were notable for their unusually progressive attitude towards female scientists, and actively encouraged women into the field of X-ray crystallography. In doing so, they enabled the careers of many women at a time when science was almost exclusively male-dominated. 11 out of 18 students in William Bragg’s research group were women.

Several of the Braggs’ students became prominent crystallographers in their own right. Kathleen Lonsdale was one of the first two women to be elected to the Royal Society (in 1945), and became the first female tenured professor at University College London.She also confirmed the structure of the benzene ring and used her status to campaign for women in science, drawing attention to the challenges of balancing family life and a career in research.

The Braggs also passed their values to their male students. Another prominent crystallographer and previous Bragg student, John Desmond Bernal, believed in equal opportunity for women and played a significant role in making crystallography one of the few physical sciences hiring significant numbers of women at that time.

The influence of the Braggs on the culture of crystallography is indisputable, with many of their tutees going on to start their own diverse and non-discriminatory lab cultures. A 1990 study argues that the Braggs started a ‘scientific genealogy’, directly extending to over 50 female crystallographers.

The ‘discovery’ of DNA

The rise of women in crystallography did not come without challenges. In 1962, James Watson and Francis Crick won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for discovering the double helix structure of DNA. The discovery is often considered one of mankind’s greatest achievements, providing invaluable evidence of the relationship between molecular structure and function in living organisms.

However, it was later revealed that Watson and Crick had used female crystallographer Rosalind Franklin’s data (the infamous ‘Photo 51’) without her consent. Franklin did not share their Nobel Prize win, and had tragically died of ovarian cancer in 1958.

In his 1968 autobiographical account of the discovery, Watson criticised Franklin’s physical appearance, and referred to her patronisingly as “Rosy”, stating that she either “had to go or be put in her place”. Critically, however, Watson also revealed what seems to have been concealed from Franklin during her lifetime, despite her long friendship with Watson and Crick: that their ‘discovery’ would not have been possible without her work. Today, Franklin is often portrayed as a feminist icon and victim of societal prejudice against women in science. While more recent research paints a more nuanced picture (she reportedly did not consider herself to be a feminist “in any modern, meaningful sense”), her experience stands as testament to the sexist attitudes that permeated science at the time. It also shows that, despite increased opportunities for women in the field, crystallography was not immune to wider societal prejudices against women.