Behind the rise: The surprising chemistry responsible for the art of breadmaking

The “rye-se” of bread

Over the past 18 month, breadmaking has experienced a surge of popularity as people look for new hobbies to explore within the home. This increase in popularity was so intense that there was actually a flour shortage across UK supermarkets in April 2020.

Over the past 18 month, breadmaking has experienced a surge of popularity as people look for new hobbies to explore within the home. This increase in popularity was so intense that there was actually a flour shortage across UK supermarkets in April 2020.

Whilst the lockdown-driven excitement surrounding it was short-lived, the skill behind breadmaking as existed for thousands of years. It likely became a staple of our cuisine when early humans began transitioning from a nomadic lifestyle to farming-based community. Today, it is undoubtedly one of the most important foodstuffs on the planet, with the British sandwich market alone valued at around £8bn.

For your average white loaf of bread, the four basic ingredients are flour, water, salt and yeast. Here, we’ll take a look at these ingredients and what function they serve.

Flour power

Flour makes up the foundation of any loaf of bread. White flour is made by first separating the different components of wheat and extracting the flour from the grain through a series of sieves. To make wholemeal flour, other parts of the wheat grain are added back into the processed flour.

Flour makes up the foundation of any loaf of bread. White flour is made by first separating the different components of wheat and extracting the flour from the grain through a series of sieves. To make wholemeal flour, other parts of the wheat grain are added back into the processed flour.

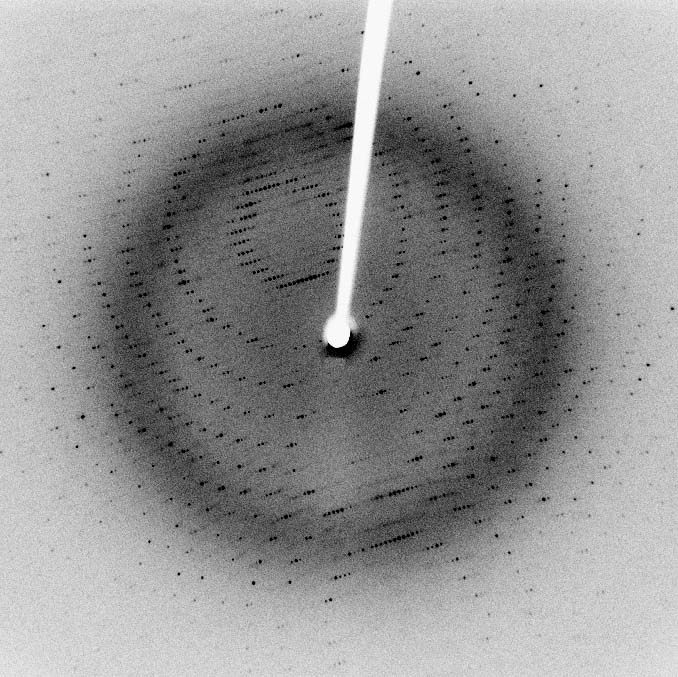

The flour found in wheat contains two key proteins called glutenin and gliadin (known together as gluten proteins). When exposed to water, these proteins interact with each other to create a large, webbed gluten network held together by disulphide and hydrogen bonds. The network is what gives bread its texture and structure. When you visit the shop, you’ll likely be surrounded by a wide variety of flours, for example ‘Plain white flour’, or ‘Strong white bread flour’. The main difference between these flours are their respective protein contents, i.e., how much gluten they contain. Strong white bread flour has a uniquely high protein content (10-13%) – this means that it has enough gluten to form the strong networks required for bread. Comparatively, plain white flour has around 8% protein content, too little to form the kind of gluten networks demanded by bread, but perfect when making light and fluffy cakes.

Flour and water alone lay the foundations of a loaf of bread, but to perfect it, salt is added both for flavour and to introduce toughness. Gluten strands have a net positive charge, so they repel each other. The salt ions can shield this charge and let strands interact more intimately – tightening the network and resulting in a more controlled loaf.

The need to knead

After the ingredients are mixed together, you then knead the bread – transforming it from a wet and rough texture to a smooth and silky one. As your work the dough, the gluten molecules untangled and straightened out, aligning them into a more evenly structured web. After tightening the dough into a ball, most bakers will leave for an hour or two – to let the yeast do its job – until it’s doubled in size. And what does the yeast do during this time, I hear you ask?

After the ingredients are mixed together, you then knead the bread – transforming it from a wet and rough texture to a smooth and silky one. As your work the dough, the gluten molecules untangled and straightened out, aligning them into a more evenly structured web. After tightening the dough into a ball, most bakers will leave for an hour or two – to let the yeast do its job – until it’s doubled in size. And what does the yeast do during this time, I hear you ask?

Last but not yeast…

Yeast are a single-celled fungi that feed on the natural sugars found in flour to produce carbon dioxide gas. The gas is caught by the webbed gluten network and inflates the bread dough, stretching out the interwoven molecules to form the hole-filled structure when you cut into a fresh, crusty loaf of bread. After the first rise, the bread is ‘knocked back’ and deflated before letting it rise once more. This removes any large air bubbles and redistributes the nutrients in bread, giving the final product a more consistent texture.

Yeast are a single-celled fungi that feed on the natural sugars found in flour to produce carbon dioxide gas. The gas is caught by the webbed gluten network and inflates the bread dough, stretching out the interwoven molecules to form the hole-filled structure when you cut into a fresh, crusty loaf of bread. After the first rise, the bread is ‘knocked back’ and deflated before letting it rise once more. This removes any large air bubbles and redistributes the nutrients in bread, giving the final product a more consistent texture.

Bready or not, here it comes

After being shaped, the dough is then ready to be put in the oven. When subjected to the intense, high temperatures found within, the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast expands rapidly outwards, pushing against the gluten network and inflating the structure to give the porous crumb found on the inside of any good-quality loaf. In the oven, the Malliard reaction also occurs, transforming the bread from a pale yellow to a warm golden-brown. The Malliard reaction is a complex series of reactions that occur when certain amino acids and sugars interact in the presence of enough heat. As well as changing the colour of the dough, the Maillard reaction helps create the toasty flavours you experience in a freshly baked loaf of bread.

After being shaped, the dough is then ready to be put in the oven. When subjected to the intense, high temperatures found within, the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast expands rapidly outwards, pushing against the gluten network and inflating the structure to give the porous crumb found on the inside of any good-quality loaf. In the oven, the Malliard reaction also occurs, transforming the bread from a pale yellow to a warm golden-brown. The Malliard reaction is a complex series of reactions that occur when certain amino acids and sugars interact in the presence of enough heat. As well as changing the colour of the dough, the Maillard reaction helps create the toasty flavours you experience in a freshly baked loaf of bread.

So next time you tuck into some ciabatta or naan with some friends, you can be that person and remind everyone about all the intricate chemical reactions that have gone into creating the loaf.